PLEASE, SLOW DOWN

For the launch of WAY MORE, Patrick Pilz offers a personal and self-critical look at how running has changed—shifting from a practice of presence and discovery to one increasingly shaped by performance, perception, and social media.

Between inclusivity and pressure, authenticity and aesthetic, this reflection asks: What have we gained—and what have we lost—when sport becomes content and health a product. Do we risk losing sight of what once made this sport meaningful? And yet, there’s hope: for movement that reconnects us—with ourselves and each other.

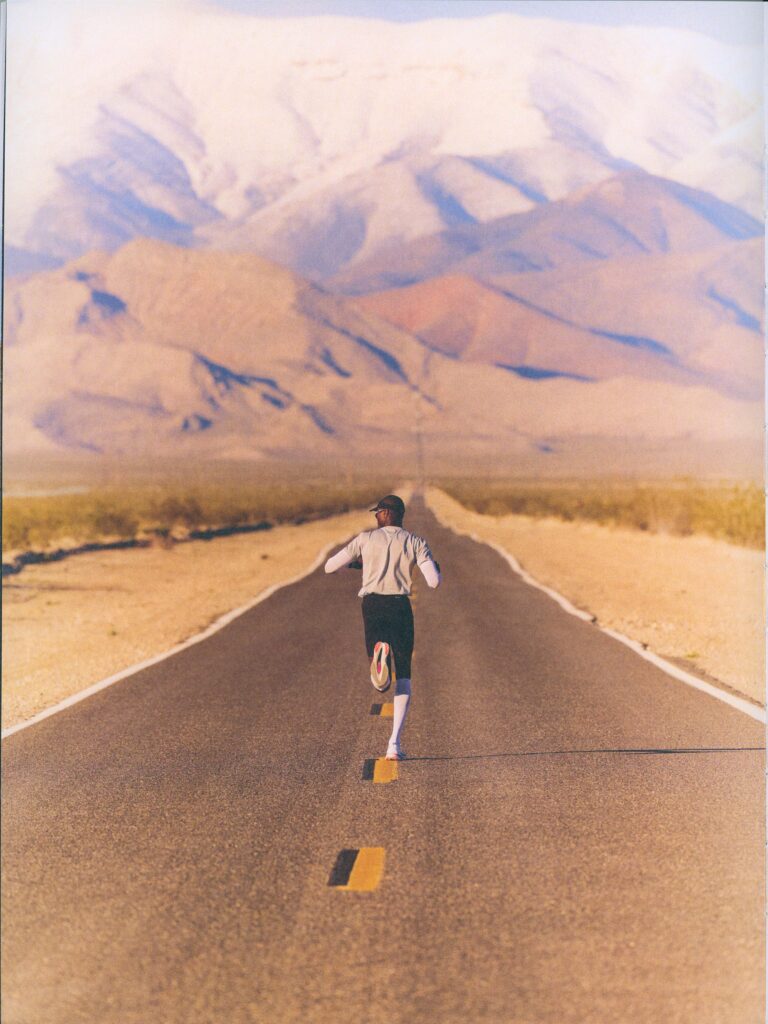

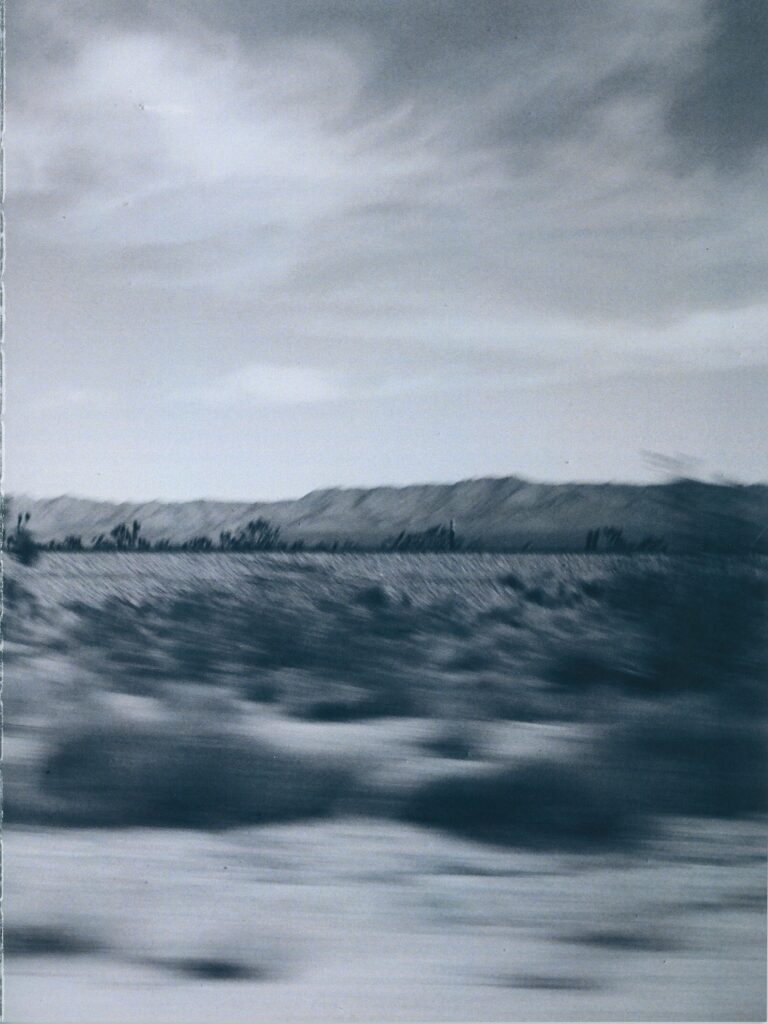

Imagine a place without any digital proof that your performance ever happened. No platform to upload a screenshot of your pace, no reels of your pre-run oats, no need to align your shoe brand collab with your training peaks. A place where movement existed in its purest form—unshared, unmeasured, unbranded.

This is not a utopian vision, but a memory. Before likes, loops, and leaderboards, there was amateur sport. A raw, honest pursuit shaped by passion and community. In the decades before the digital age—particularly before the widespread adoption of the internet and social media in the late 1990s and 2000s—sport, especially in its amateur form, was far less commercialized. Without the constant gaze of digital platforms, performance existed in quiet spaces: local clubs, empty training halls, early morning lanes. It was about effort, identity, and belonging—not image or monetarization. It was about chasing sport dreams, not content plans.

I sometimes think back to those days—long before I was part of them—and wonder what it must’ve felt like to push your limits without ever having to prove it to the internet.

I won’t pretend I come from a time before social media—but I do come from a time before it became a stage. In those early digital days, the online world felt more like a quiet rehearsal space than a public arena. ICQ crackled through dial-up modems with its iconic “uh-oh”—a lo-fi signal of connection across adolescent training groups and post-session exhaustion. SchülerVZ and early Facebook offered places to archive memories, not build personas. Training camp albums lived in pixelated stillness—shared with those who were there, not a broader audience. MySpace and YouTube gave us the soundtrack to our sessions—manually hunted, downloaded, burned to CD. And the YouTube clips of our sporting idols at World Cups or the Olympics lit the fire in us. They shaped dreams and formed references. We lived digitally, but not yet performatively. We trained without thinking of cameras. We moved for the moment—and for each other.

I grew up in the world of competitive rowing—a sport with deep roots. It was one of the first organized sports brought to Germany by British merchants in the early 19th century, arriving in Hamburg and laying the foundation for what would become the German club system. Before that, physical activity was largely confined to military training and nationalist gymnastics movements, particularly those promoted by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, whose ‘Turnen’ was more a tool for discipline and patriotic education than for recreation or personal growth. Rowing feels like it’s remained in that earlier time. It’s old, traditional, and almostuntouched by the currents of modern commercialism – at least in Germany. And in this world, I was lucky to grow up.

There were no commercial goals. In fact, it was almost frowned upon to make money from the sport. The experience of rowing in this space felt deeply personal—almost sacred. Training was marked by intensity, repetition, and presence. Long sessions on still lakes, early mornings wrapped in fog, blades cutting silently through the water. Sometimes shared with others in perfect synchronicity, sometimes alone, navigating your thoughts as much as your course. The rhythm of the strokes, the sound of the shell gliding, the burn in the legs and lungs—it created a state of deep immersion. Rowing became a space of mental quiet and total physical engagement.

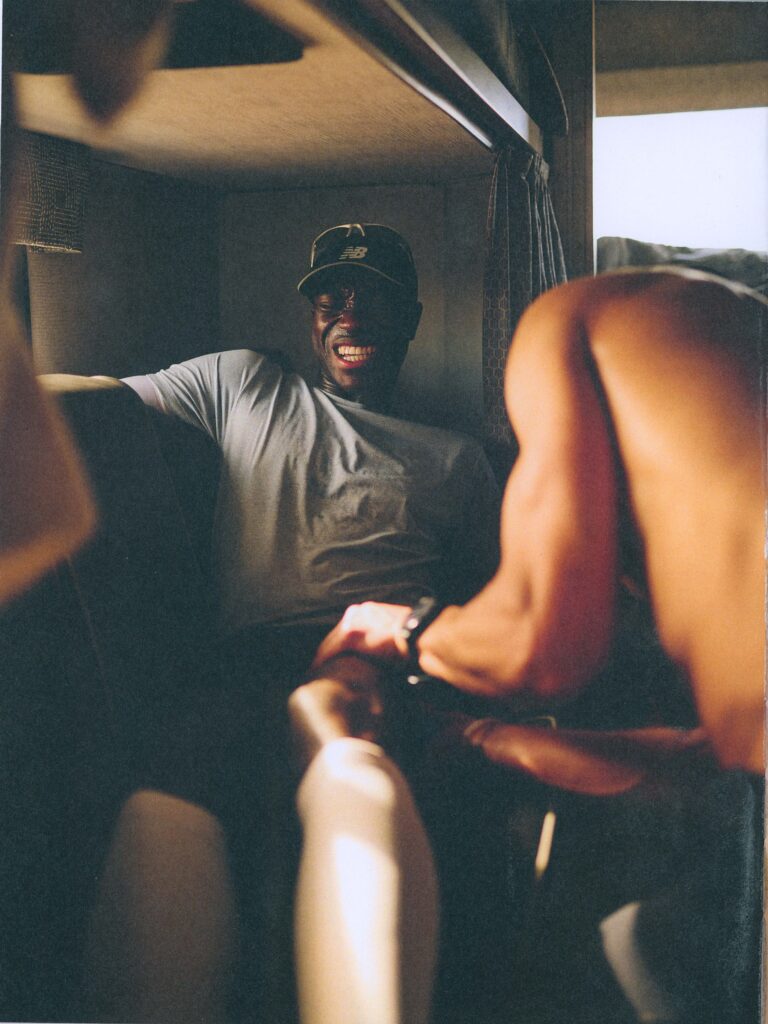

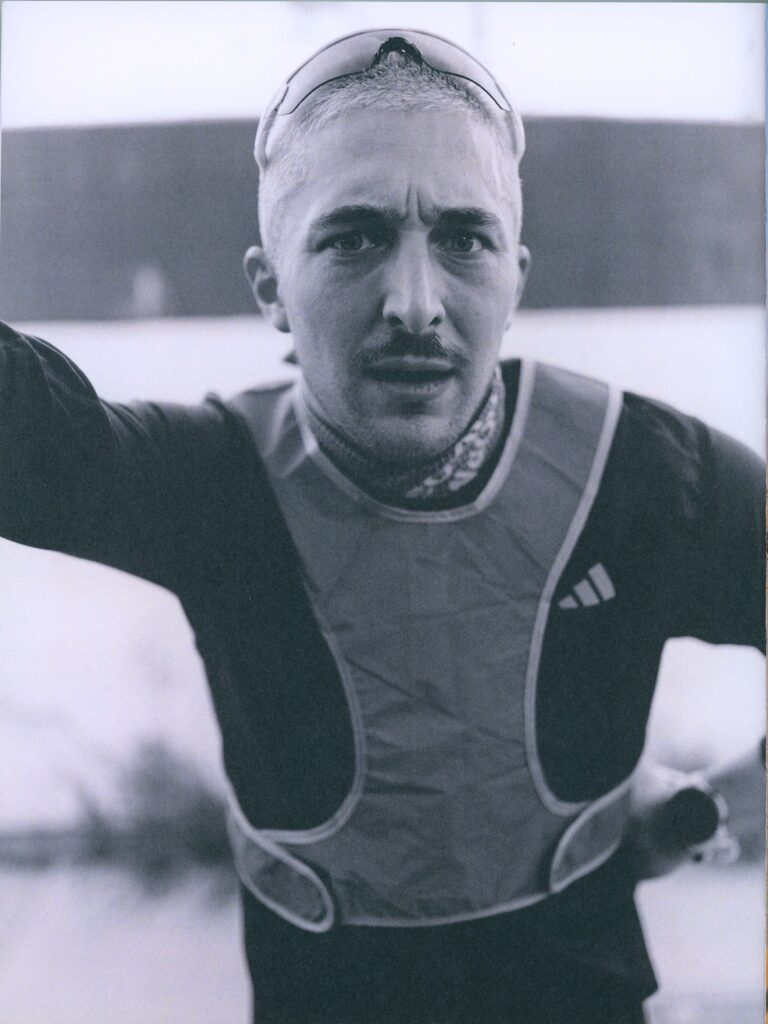

Photography entered my life during that time. In a world where everything was physical, visual storytelling became my mental refuge. I was drawn to the aesthetic of movement—bodies intension, exhaustion as expression, the fragile beauty of someone pushing through the edge. Photos allowed me to capture what words or training logs never could.

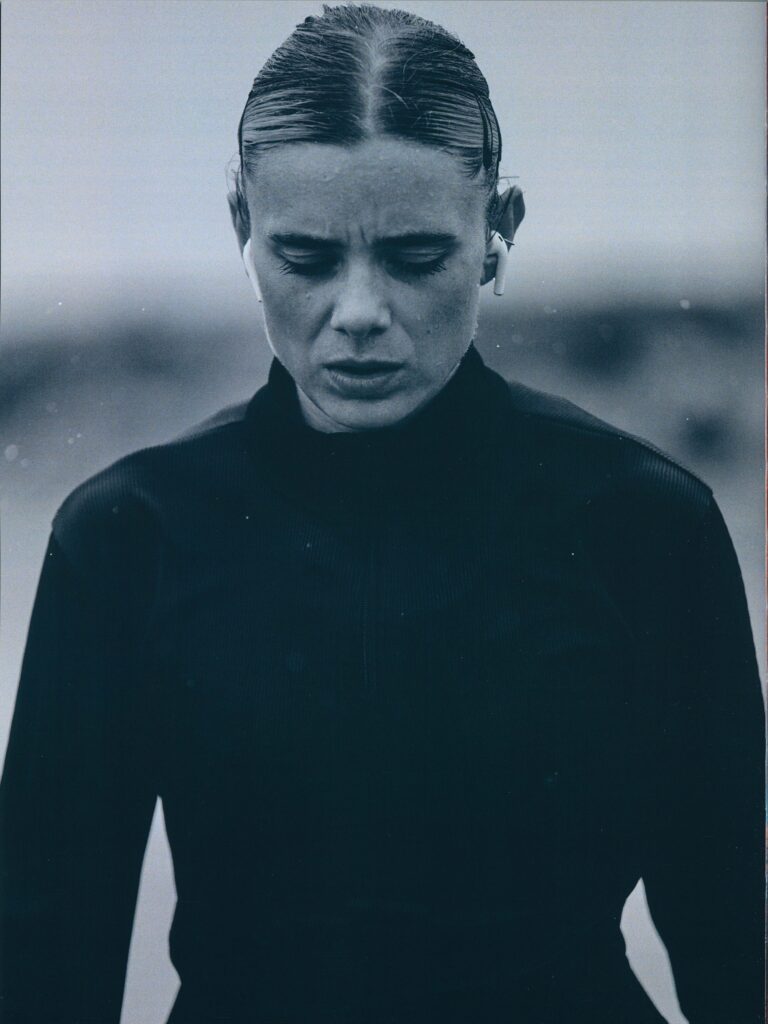

And then there were the races. Rowing competitions start like sprints—furious from the first stroke, with every crew trying to gain a psychological edge through early dominance. The boat moves backwards, and falling behind early means losing sight of your competitors. Those who lead can control the field. It’s a mental game disguised as a physical one. Over the course of six, seven, sometimes eight minutes—depending on boat class, wind, and water—your body enters a space of complete depletion. At the elite level, you see athletes collapsing across the finish line, their eyes scattered, their limbs no longer moving with intention. The body twists into forms that seem almost unfamiliar—humbling, haunting, strangely beautiful. These were the moments I wanted to hold onto.

This was the world I came to know—not just as an athlete, but as an observer. It was in this space that I began photographing. Amid all the discipline, exhaustion, and repetition, I found moments that felt almost quiet. The tension in a forearm, the twist of a torso, the stillness before the start. Photography became my way of articulating what I couldn’t yet express with words—the fragility, the power, the strange intimacy of eff ort. While my body trained, my mind wandered with my eyes pointed through lenses. And that’s where something else began to grow.

Looking back now, I realize my identity in sport wasn’t built on principle or philosophy. It was built on belonging. The sport gave me a social framework, a language, and a place. The rituals—especially the unhealthy ones—became normalized. From under-eating to overtraining, from silence about pain to the glorification of sacrifice. We didn’t question them. They were passed down, reinforced by the people we admired, and accepted as truth. We believed because it was real. But perhaps the measure of identification with sport became too strong. I wonder now if I lost sight of the human behind the athlete—the softness amidst the toughness in sport. If I confused performance with worth, and forgot that our value lies not in output, but in our capacity to feel, to care, to break, and to begin again.

That reflection came painfully. A close friend, an athlete I admired deeply for his physical strength and mental resolve, took his own life—suddenly, and without warning. He had been silently battling a late-diagnosed depression. I was shattered. It forced me to look at sport not only as a space of achievement, but as one where pain often goes unseen. I began to question the culture we had embraced. What does it do to your mind when everything you are is measured, timed, weighed, ranked? When your value feels tethered to output?

I don’t think there was one singular moment that changed everything. But there may have been a tipping point—a slow, quiet shift when I began to care more for the human dimension behind the performance. I needed space. Distance. I was afraid that sport had become too large a part of me, that my identity had narrowed down to a single lens. What if sport—so all- consuming, so glorified—left no room for anything else in a life that should be full of cultural, social, and intellectual possibilities? That question didn’t just hover—it unsettled me. It made me step back, and slowly, I began to untangle my identity—from the stopwatch, from the numbers, from the unspoken rules.

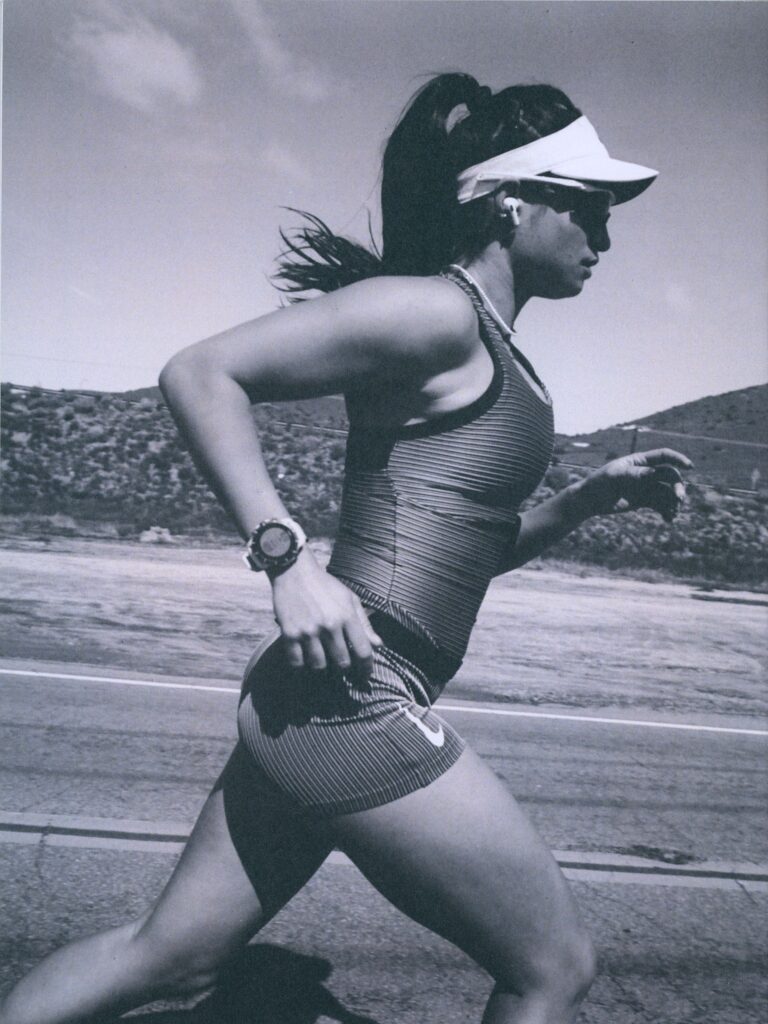

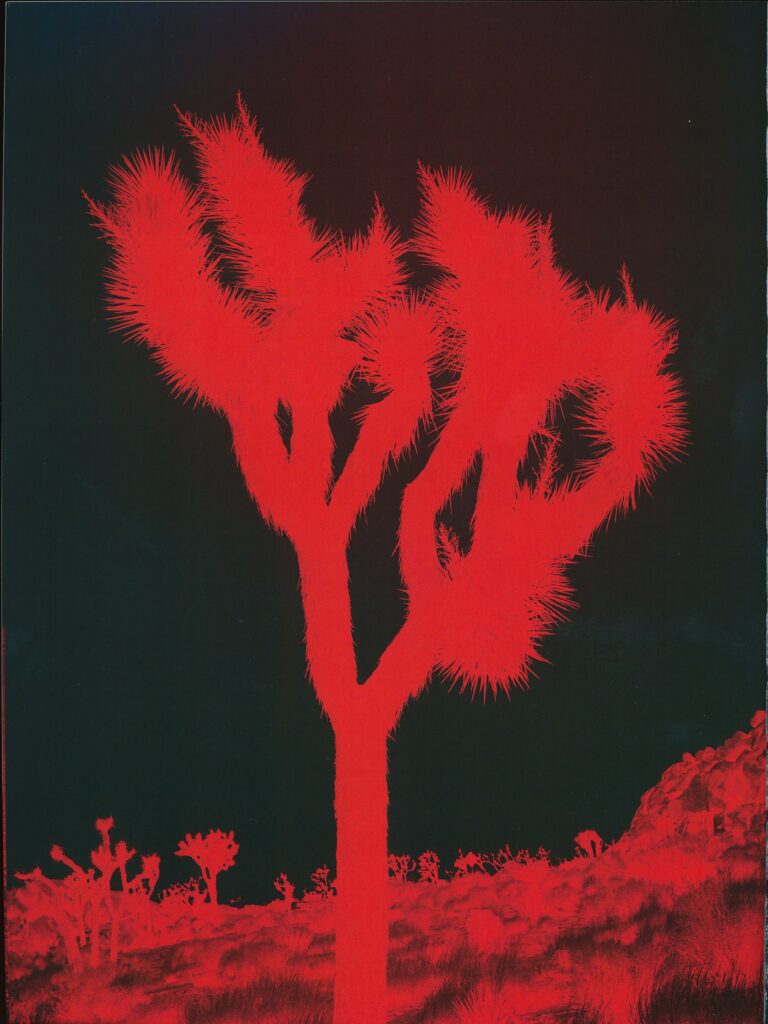

Now, more than ten years after my last rowing race, the world of sport has changed. Running has become cultural—cool, expressive, and surprisingly creative. The lines between fashion and sport have blurred, giving rise to a movement where these two worlds are no longer separate but deeply intertwined. This fusion, driven by visionary minds, artists, and brands, has opened new possibilities: a space where self-expression takes precedence over status, and where individuality can thrive.

Sport is no longer confined to traditional metrics or aesthetics. It has been reframed—as a stage for identity, a vessel for storytelling, a form of movement that is stylish, accessible, and deeply personal. Through social media and digital platforms, this evolution has birthed an aesthetic that resonates widely, inspiring new communities that gather around shared values and curiosity rather than performance alone.

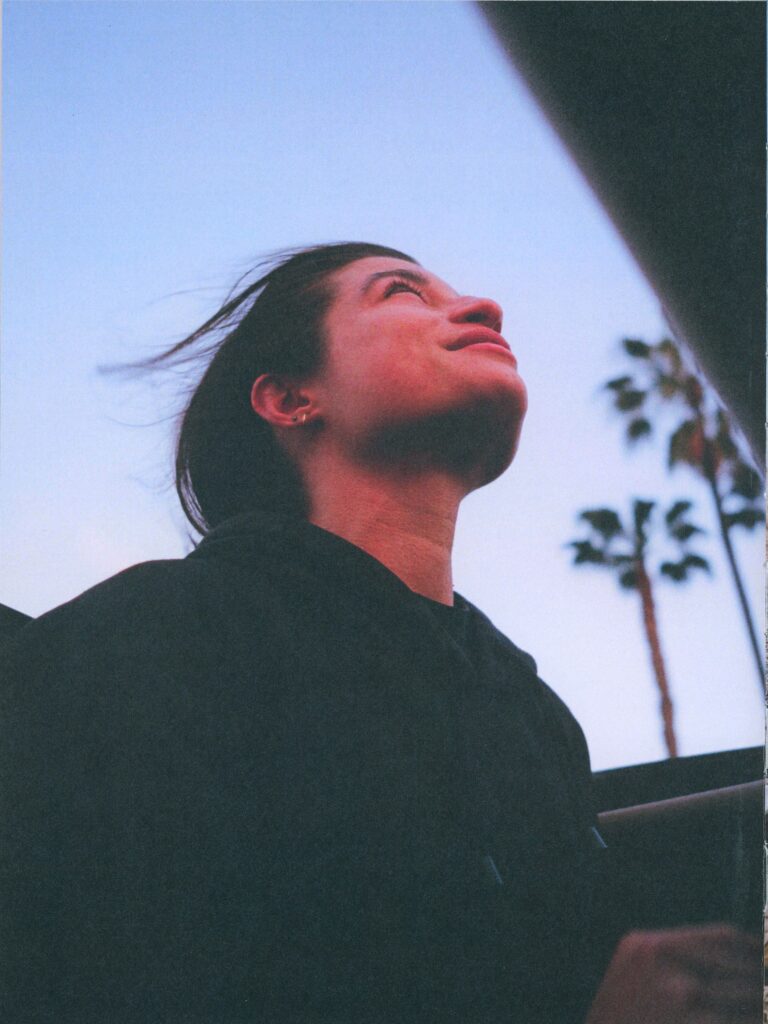

More and more people enter running today not through elite federations or hierarchical systems, but through grassroots initiatives, collective energy, and shared joy. It’s no longer just about how fast you are, but about how deeply you connect—with your body, your surroundings, and the people around you. That shift, for all its complexity, holds real promise. But beneath the surface of this cultural wave lies a more complex dynamic. What once was about pace and performance is now also about presence and perception. Not just how fast you run, but how well you document it. Who you collaborate with. How many people care. Performance has become layered—part physical, part aesthetic, part algorithmic.

The rise of digital platforms, while instrumental in amplifying this cultural shift, has also brought with it a distorted and fragmented view of reality. Growth-driven brands and meticulously curated content now shape how we perceive success, belonging, and achievement. Social media, for all its connective power, often imposes unrealistic standards and invisible pressures—pressures that mirror, in subtle new ways, the same demands we once internalized as athletes. “Train harder, eat less, show no weakness” has morphed into “post more, grow faster, stay visible.” The platforms have changed, but the underlying anxieties remain familiar. In both eras, we are asked to perform. In both, it becomes easy to lose sight of the person behind the metrics.

What worries me more deeply is the larger system beneath these cultural shifts. In this endless pursuit of optimization and visibility, I fear that even our moments of vulnerability are being transformed into performances. Slavoj Žižek captured this phenomenon incisively in an interview with The New Yorker, cautioning that we might believe we are expressing ourselves— yet too often, our authenticity becomes aestheticized, commodified.

As Erich Fromm poignantly outlined in To Have or to Be? , our modern society is built on the illusion that having—owning, producing, achieving—is the path to being. The result is a collective forgetting: we confuse visibility with value, optimization with meaning. Sport, which once offered presence and process, risks becoming another space governed by extraction and growth. Another metric. Another marketable trait.

Fromm’s critique resonates sharply in the world of contemporary athletics and wellness culture. When the act of running becomes content, and health becomes a product, we are no longer in movement—we are in performance. We begin to pursue not the inner experience of sport, but the outer validation it can provide. And slowly, quietly, we unlearn how to simply be in our bodies. How to move without measuring. How to strive without broadcasting. We begin to lose access to the very thing that made sport meaningful in the first place: its capacity to ground us, to slow us, to return us to ourselves.

And yet—I remain hopeful.

Because sport still has the power to connect us to ourselves and to each other. WAY MORE is my attempt to reclaim that space. A photographic reflection on movement, meaning, and identity. A place to pause, to think, to feel. To remember that sport is not just a means to an end, but a language. One that says: I am here. I am moving. And that is enough.

—Patrick Pilz

Get your copy of WAY MORE here: https://forms.gle/DMa3nVyBkD6DpC9r8